Books & Benefactors: Brought to you by HMRC

Sinead O’Riordan reviews Book and Benefactors, the latest exhibition at The Brotherton Library, University of Leeds.

You might not have noticed, but there is a gallery space that watches you as you get your cheese panini in Parkinson Court. Treasures of the Brotherton, located in the right wing of Parkinson, is home to exhibitions curated using the material from the University of Leeds’ own Brotherton Special Collections.

The latest collection of items donated to the Brotherton Library makes up ‘Books and Benefactors’, an exhibition open until 6th April 2024. All objects were brought together by wealthy industrialist and contemporary of Edward Allen Brotherton, and Sir Thomas Edward Watson (1851-1921). His collection, from the oldest item to the newest, spans a millennium and displays treasured manuscripts rarely seen.

This exhibition is unique in the fact it foregrounds the method through which these artefacts have come into Brotherton Library’s possession. Thanks to a scheme by Arts Council England and HMRC (His Majesty’s Revenue and Customs), objects of high cultural significance are donated to national institutions instead of inheritance tax. It’s called Acceptance in Lieu (AiL) and definitely provides a certain fiscal je nais se quois to the exhibits. When money is in short (or stubborn) supply, you can always donate a spare Michaelangelo to write off some tax.

Collections exhibited in British museums and galleries have infamously come under scrutiny for how they turned up there. The answer is usually hidden but assumed to be because of ‘colonial activities.’ With Books and Benefactors, the answer stares you in the face: money!

So, The Gryphon were invited to come to the exhibition open. I wandered into Parkinson Court, put my coat on a hanger, grabbed a glass of red wine, and began to feel part of something. There were a couple of speeches made about the exhibition which provided some interesting context about Watson himself. Deliberate or not, a sense of kinship between Watson and Brotherton was highlighted. Both were from humble beginnings, both made a lot of money from classic Victorian ventures (coal, gas, cattle) and both were part of the vanguard of the ‘new type’ of manuscript collection.

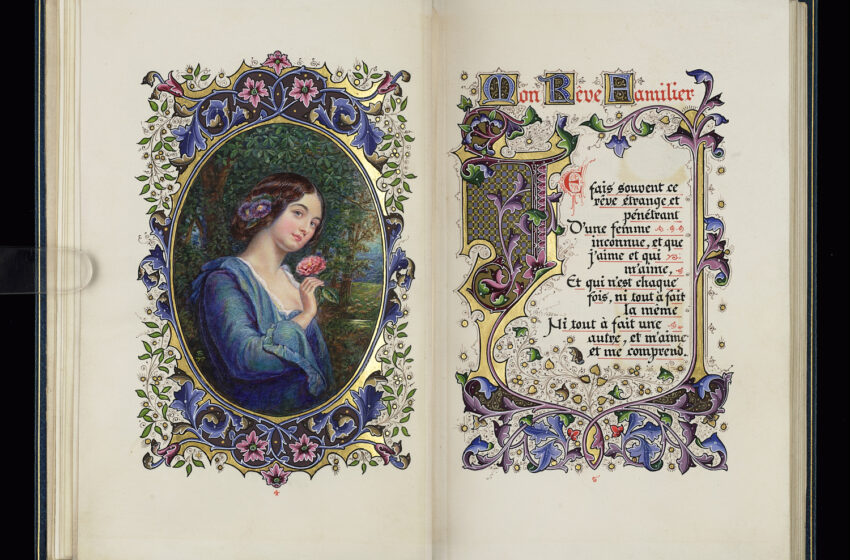

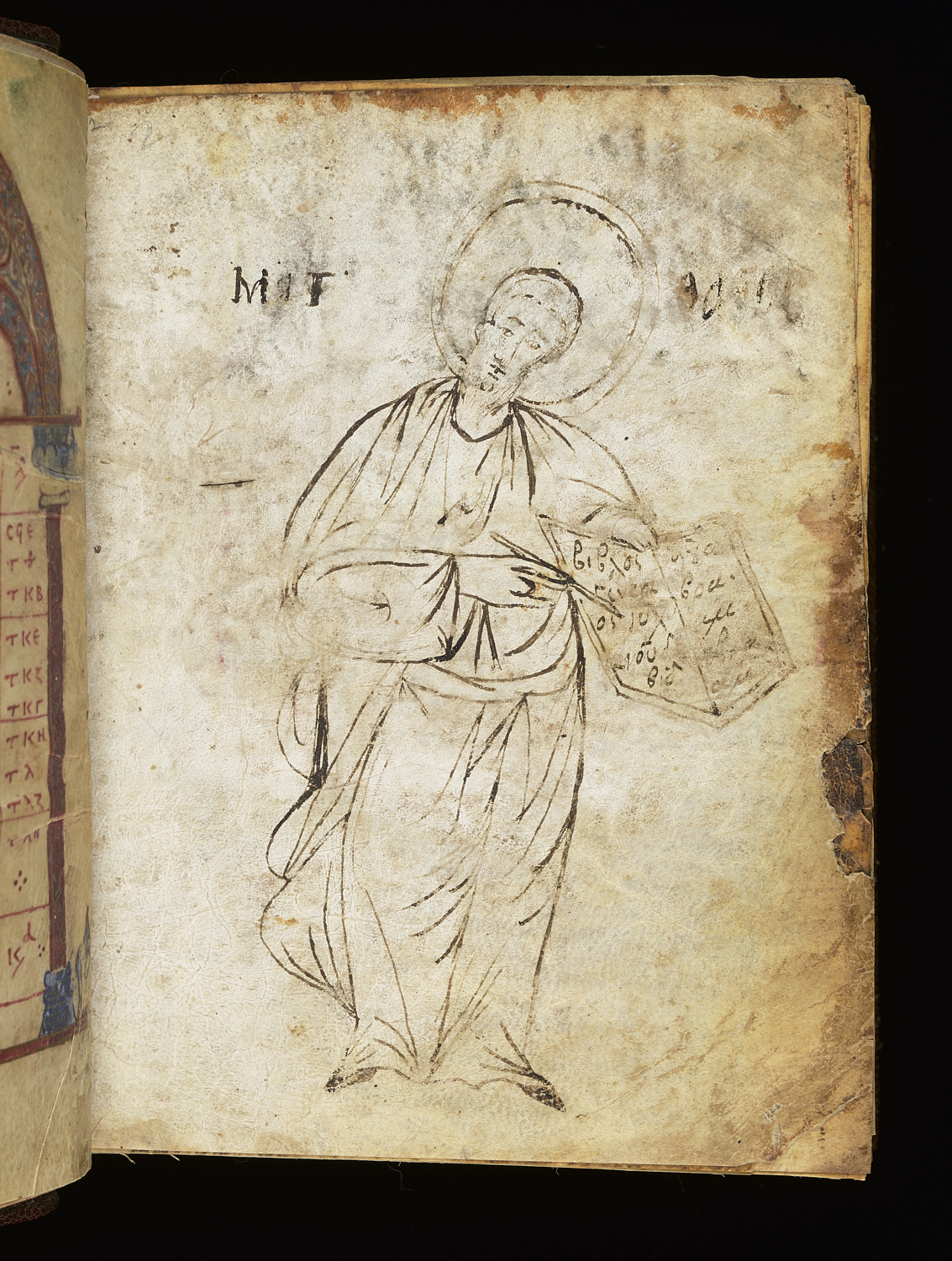

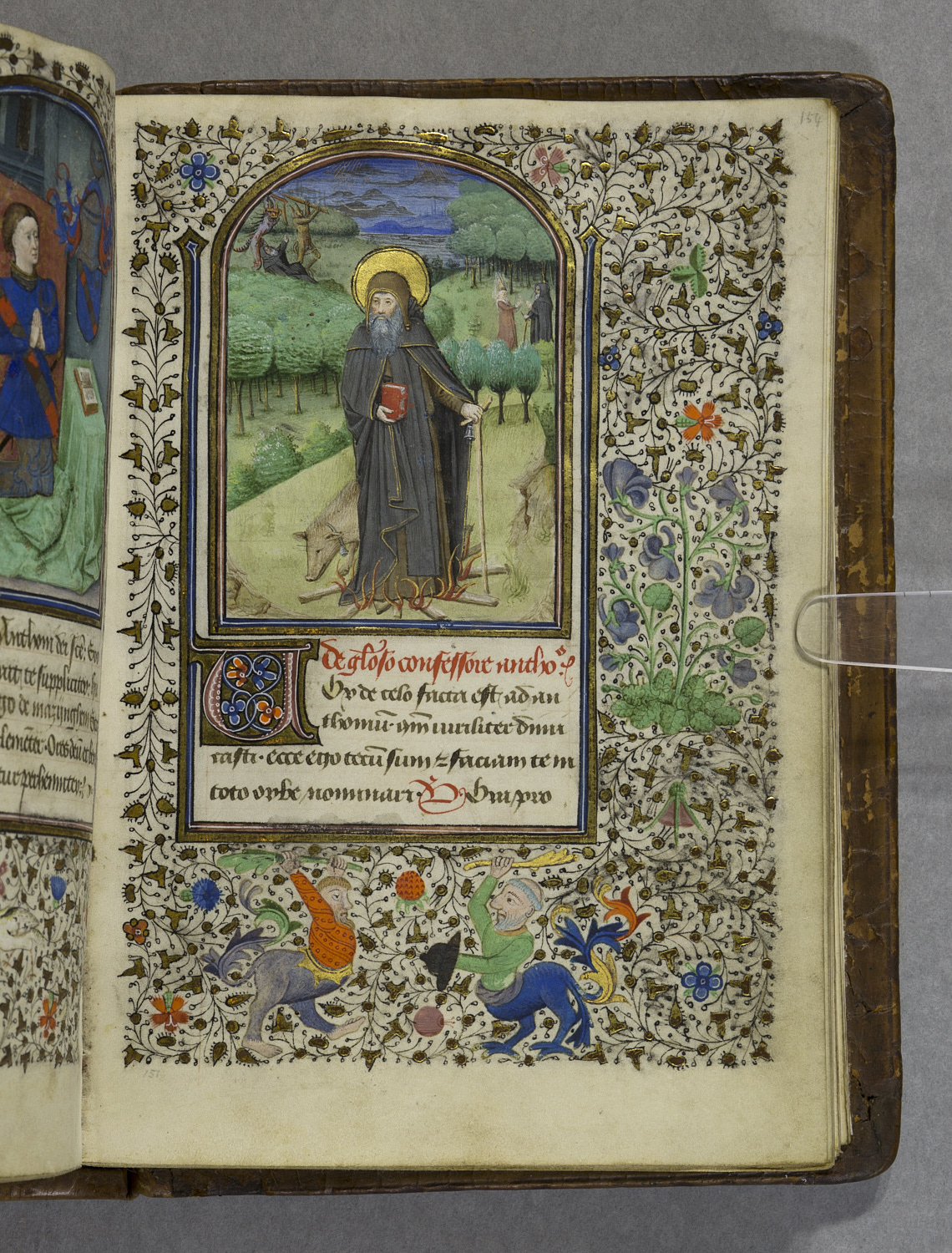

Watson’s collection is, admittedly, impressive. A Greek gospel book from Byzantium (c. 950-1050) is now the oldest manuscript in the University’s collection. The medieval ‘Brut Chronicle’ is one of only thirteen surviving copies and also includes some original Beardsley artwork.

So, the wine was drunk, and the speeches heard- it was time to see some manuscripts. The light criticisms I had of the AiL scheme were forgotten once I saw the objects on display. As always, the collection is far more interesting than the collector. Seeing the fraying on the edge of the paper and the detail of hand-drawn illustrations from hundreds of years ago brings the objects to life. The gallery provides touch-screen tablets with more information about each object, and material reconstructions of objects you can touch and feel. It is quite an immersive experience- only the blasting ringtone of ‘Brown Eyed Girl’ by one of the exhibition-goers pulled me out.

Even with this relatively small exhibition, you are taken on a tour of human history, made clear by the chronological curation of the objects from earliest to latest. Naturally, religious and ornamental texts feature heavily in the collection but so do ones that were used practically. A logbook from early airplane flights, ration book stubs, and a map of old London are all on display.

I would recommend going to see the collection. I liked it anyway. The manuscripts are interesting and the concept is refreshing. Who knows what the University might get next? Only HMRC knows.

Words by Sinead O’Riordan / Edited by Mia Stapleton

(Image Credits: Leeds University Library)