A Promising New Malaria Vaccine

Oxford University researchers and their collaborators have created a malaria vaccine that has the potential to “change the world”.

The promising new R21/Matrix-M malaria vaccine advances the worldwide effort to fight the mosquito-borne illness that causes children’s death every minute. Charity Organisation Malaria No More stated that thanks to these recent advancements, malaria deaths among children may be eliminated “within our lifetimes.”

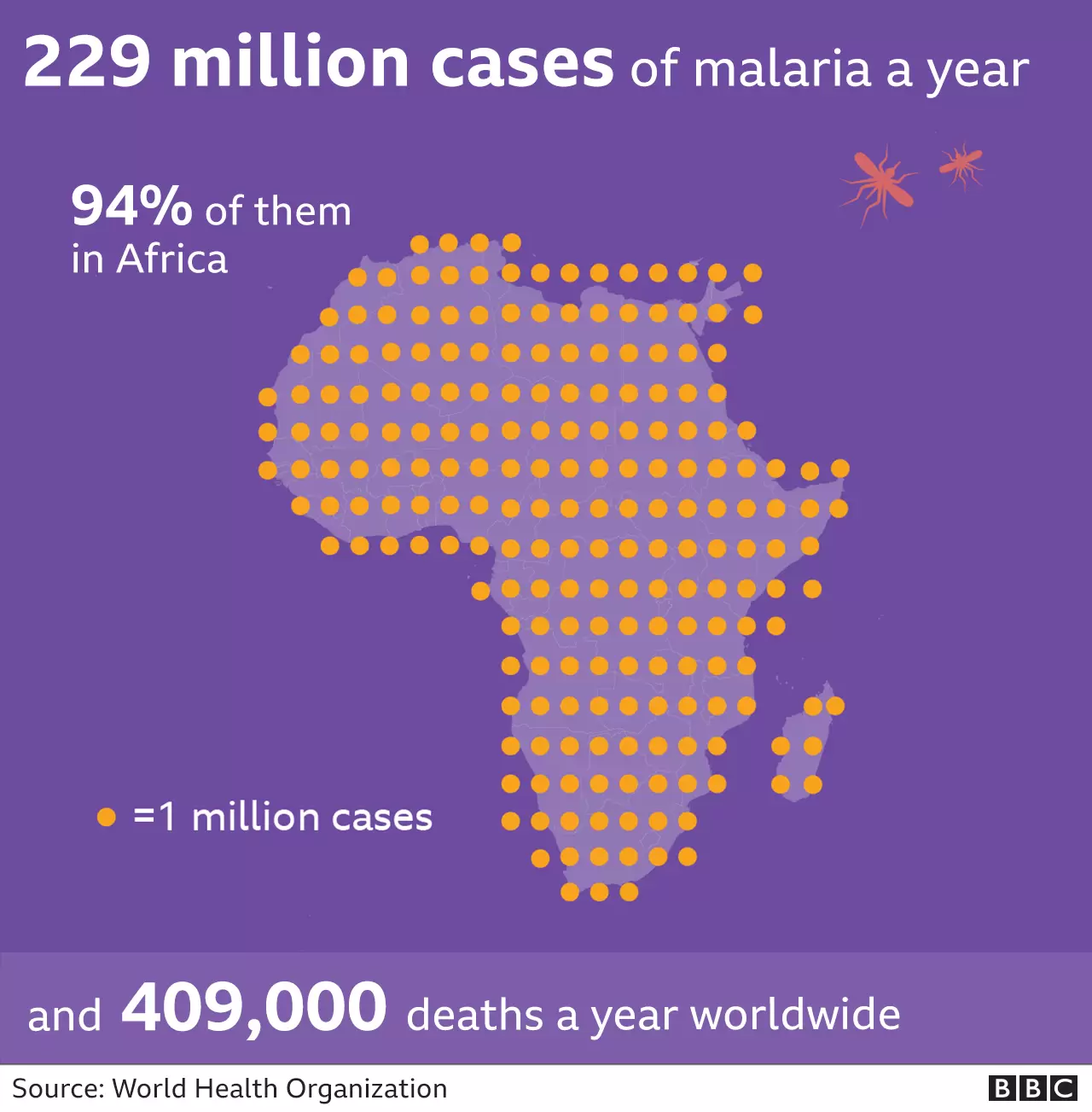

The malaria parasite is carried by the female Anopheles mosquito. Due to the parasite’s extraordinary complexity and elusiveness, it has taken more than a century to create viable vaccinations. The parasite is dynamic, making it very challenging to develop an immunity against it. Despite the $3 billion spent yearly on insecticides, bed nets, and anti-malarial medications, malaria kills over 600,000 people each year.

In the 1980s, The World Health Organization (WHO) authorised Mosquirix, the only licensed malaria vaccine, produced by British company GSK. This paved the way for the Oxford researchers to develop another vaccine, called R21/Matrix-M (or R21/MM). The Lancet Infectious Disease journal reported data from mid-stage research on more than 400 young children who received a fourth Oxford shot dosage following the first three-dose protocol. The study found that 12 months after the fourth dosage, vaccination efficacy was 80% in the group that received a greater dose of the immune-stimulating adjuvant and 70% in the group that received a lower dose.

These results contribute to achieving the WHO’s Malaria Vaccine Technology Roadmap target of a vaccine with at least 75% efficacy. There were no reported severe vaccine-related side effects.

Currently, the vaccines are in a significant Phase III experimental phase, which aims to licence the vaccine for general usage. This licensing trial involves 4,800 children with different patterns of malaria exposure at five different sites across Africa. These results will be used to compare the drug’s effectiveness and safety on a wide scale. According to interim data (collected in areas where malaria is a concern all year round, as well as those where infection is more seasonal), the vaccine demonstrated over 70% effectiveness.

It is important to note that the duration of the vaccine’s potential protection is not yet known. Researchers will continue to gather information to provide more comprehensive findings before the year is over.

As a bigger Phase III study is still underway, it is challenging to draw direct comparisons between the two vaccines. According to late-stage trial data reported the previous year, Mosquirix was ~63% effective against clinical-stage malarial infection.

Given that the two vaccinations have not yet been compared in an experimental setting, any comparisons made are still preliminary. However, Phase II results indicate that the Oxford injection is a more sophisticated therapeutic in terms of effectiveness and immunity maintenance. Moreover, the researchers are hoping that the vaccine will be licensed for widespread use in the first half of 2023. R21 also has manufacturing superiority.

The Serum Institute of India (the world’s biggest vaccine producer) has pledged to manufacture +180 million vaccines once approval is received. This is roughly 30 times the amount of Mosquirix produced each year.

It is now common knowledge that climate change is increasing the risk of vector-borne illnesses worldwide. Many of these illnesses are chronic, incapacitating, and stigmatising, feeding into the already dire problems of poverty and inequality.

Accelerating the development of vaccines and treatments, whilst also making them accessible to the most afflicted regions is an important course of action. Results of R21 vaccine studies provide optimistic evidence. It is hoped that, with the correct assistance, it could result in malaria-related child fatalities being eradicated within our lifetimes.