The Desecration of Dahl: Why we shouldn’t appropriate old literature

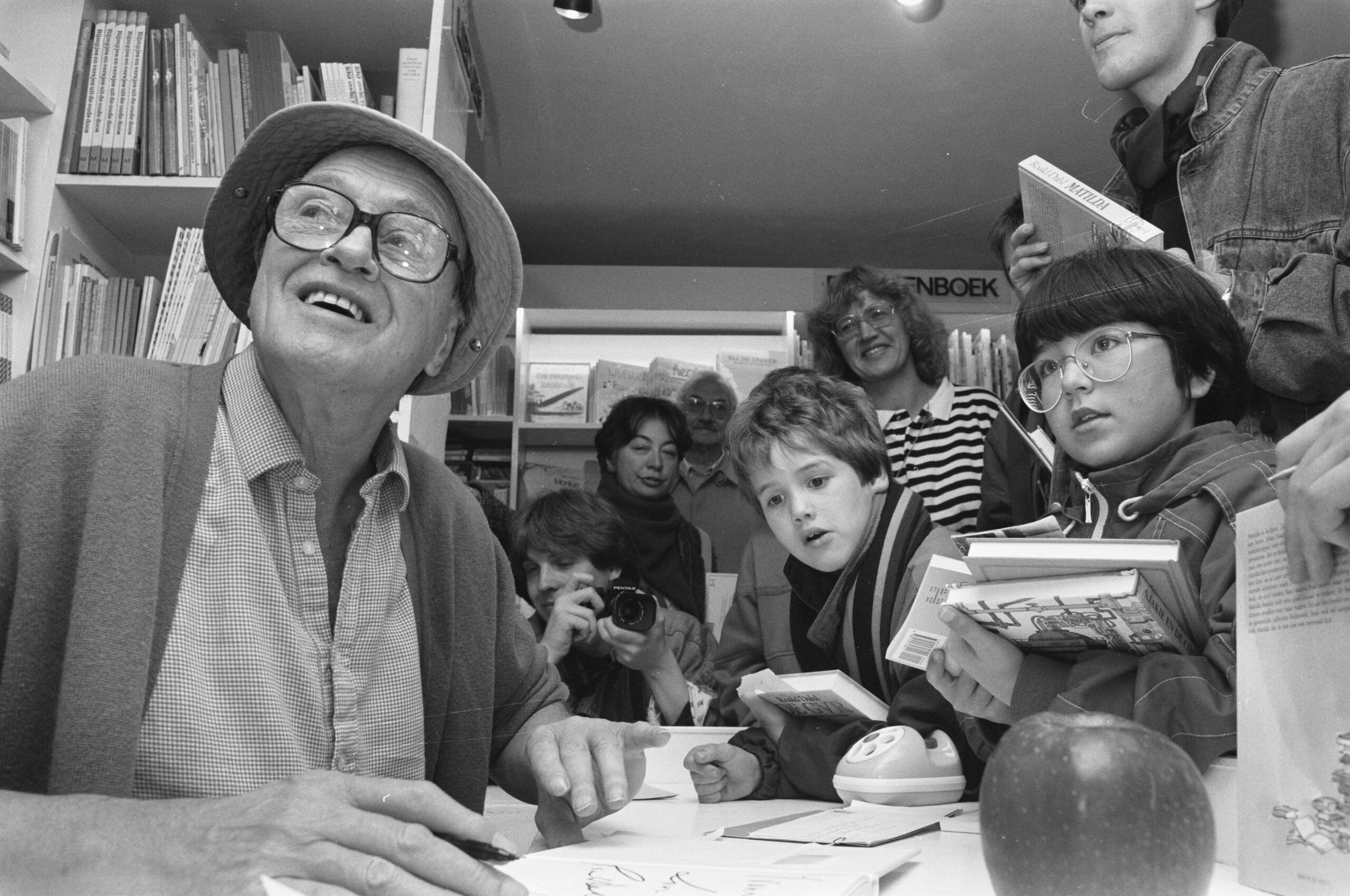

Roald Dahl was my first introduction to literature. His easy-to-read novels ignited a love for words that has carried through to my twenties. That began with the likes of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, Fantastic Mr Fox, James and the Giant Peach, The BFG and his other exceptionally great literary artefacts. It seems to me that Dahl’s lasting appeal is a result of his outstanding talent for tapping into children’s fantasies and fears and laying them out on the page with a sort of anarchic charm. Adult villains are drawn in terrifyingly relatable detail, before they are exposed as liars and hypocrites, and brought tumbling down with a retributive narrative arch. This is usually the result of either sudden magic or the superior acuity of the children that they abuse. It is, in a way, an empowerment for children to recognise their potential power over their superiors.

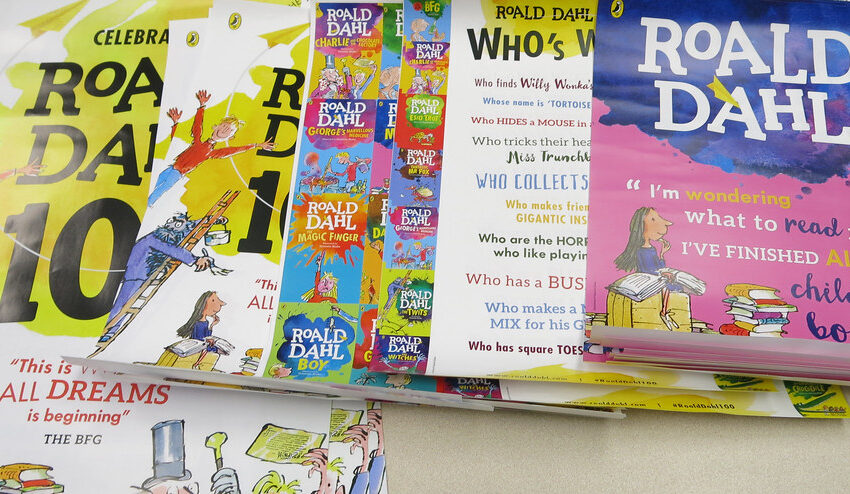

Sadly, a handful of Dahl’s brilliant novels have recently fallen victim to the chopping block of illogical modern-day wokeism. New editions of the classic books now available in bookstores show that some passages relating to weight, mental health, gender and race have been altered by Puffin Books, a division of Penguin Random House, with consent being granted by the Dahl estate. In Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, first published in 1964, Charlie’s greedy antagonist Augustus Gloop is now no longer “enormously fat,” just “enormous”. In a similar vein, Mrs Twit in The Twits isn’t “ugly and beastly” anymore, just “beastly”. Gender-neutral terms have also been added. Whereas Willy Wonka’s workers, the Oompa Loompas, were initially described as “small men,” they are now “small people”. Words like “crazy” and “mad” have been omitted, lest they appear to make light of mental health problems. In the new edition of Witches, a crooked necromancer who is posing as an ordinary woman may be working as a “top scientist or running a business” rather than as a “cashier in a supermarket or typing letters for a businessman”. Clearly, the modern agenda requires that we promote witches in STEM, rather than women. Another entirely questionable revision is that Fantastic Mr Fox’s three sons are now his three daughters. Why? Dahl wanted him to have sons, so it should remain that way.

Worse still, the word ‘black’ has been removed from the description of the terrible tractors in the Fantastic Mr Fox, released in 1970. The machines are now simply “murderous, brutal-looking monsters”. Yes, you read that correctly. An inanimate object, whose colour happens to be metallic black, has somehow been purged in the name of antiracism. Likewise, characters no longer turn “white with fear”, and the Big Friendly Giant no longer sports a “black cloak”. The patronising urge of the sensitivity police to protect ethnic-minority children from certain words is infinitely more insulting to them than Dahl’s tales could ever be. These words are descriptions of things, feelings and objects; never are they being used to denigrate or harm any group or person.

These ludicrous emendations to tailor to twenty-first century sensibilities massively risk undermining the genius of great artists and preventing readers from confronting the world as it is. If you weren’t concerned about the moral and practical implications of cancel culture before, then surely this appalling censorious attack on some of the best-known children’s books of the modern era should cause you to question it entirely. Puffin’s purging of Dahl’s literature was carried out in conjunction with the organisation Inclusive Minds, a collective of sensitivity readers who are “passionate about inclusion and accessibility in children’s literature”. Their use of the word ‘inclusive’ is somewhat ironic, however; excluding problematic people and hard-to-swallow ideas seems to be a prerequisite of their concept of inclusion. What is most striking about the Dahl case, however, is that they arrived on the wrongspeak crime scene after publication – nearly half a century after publication, in this case. Normally they’re there before publication.

Numerous publishers of children’s books now employ sensitivity readers to pore over authors’ manuscripts and ensure there’s nothing that might offend the young, or any groups for that matter. The lack of artist autonomy is also a moral concern, here. Dahl’s been dead since 1990. The posthumous appropriation of his fun and fictional world by a fleet of vain and lofty censors is egregiously wrong, on a moral and an artistic level.

In saying this, I do not intend to put Dahl on an untouchable pedestal; he was by no means an angel. While famed for his collection of children’s novels, Dahl was also the author of the controversy-ridden My Uncle Oswald; a book defined by its unremitting misanthropic language, graphic sex scenes, and highly dubious sympathy for eugenics. The bizarre novel follows Oswald and his accomplice, Yasmin Howcomely, as they travel Europe, drugging men with a homemade beetle powder that makes them detrimentally horny. This spiking allows Oswald and Yasmin to harvest the men’s sperm in the hope of selling it to rich, childless women. It is far from a subtle book. At the time of its release, many criticised it for its overt glorification of rape culture, sexism and apparent homophobia. Perhaps this suggests that Roald Dahl can never be made ‘nice’, so why try?

Censoring old fiction creates more problems than it manages to solve. If the aim of this is for a more inclusive education through literature, then it begs the question: when does one stop learning? Even as adults, we are constantly learning and revising our ideas, opinions and general worldview; very few are staunchly set in their own ways for eternity. Need we amend and censor the likes of Bret Easton Ellis’ American Psycho, which is plagued with cruel and revolting imagery? Does publisher Pan Macmillan worry that adult readers might suddenly become violent misogynists? It becomes impossible to draw a line between what is able to be censored, and what isn’t. I fear that as the years pass, arrogant alterations on the world’s best-loved writers will only become more commonplace. This slippery slope ought to be avoided if respect for artistry is to be upheld.