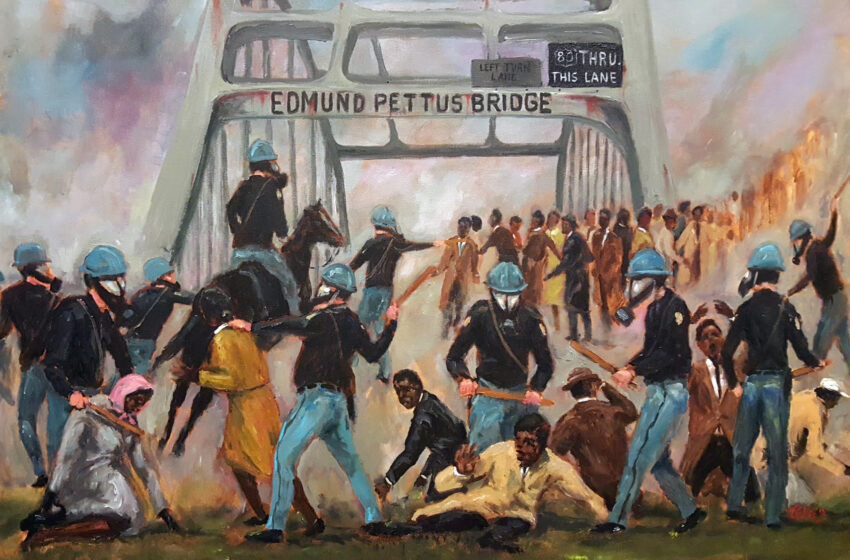

Bloody Sunday, 50 years on. An embodiment of British historical neglect towards Northern Ireland.

Today, Sunday the 30th of January, marks the half-century anniversary of Bloody Sunday, also known as the Bogside Massacre in Derry, Northern Ireland. The massacre carried out by the British army resulted in the deaths of 14 innocent protesters in the Bogside, and a further 12 civilians suffered life-changing injuries. Ask many British people about Bloody Sunday, and they have never heard of it.

Understanding how the events of 30th January came about requires some background context. At the time of the massacre, Northern Ireland was cascading into a brutal conflict that involved the two principal communities of the country, the Nationalists who were largely Catholic, and the Unionists who were predominantly Protestant. Northern Ireland’s existence as a nation was constitutionally unfavourable to the Catholic community who were the minority. Voter suppression and gerrymandering amongst other problems caused by the British occupation of the six counties had resulted in a Civil Rights movement in conjunction with that of the USA in the late 1960s, as the Catholic minority protested its living situation in the country. Community tensions spilled over as a result of the Civil Rights movement and paramilitary organisations were established on both sides of the divide. The British government’s response to the tensions of the late 1960s was to send over British troops to occupy the country and try to bring some harmony to a rapidly deteriorating situation.

The complexities of the conflict in Northern Ireland and the centuries of history that predate the events of the Troubles add to the convoluted political landscape of the early 1970s. Warring paramilitary groups claimed civilian deaths and atrocities in their intense struggle against each other, with the presence of the British army only exacerbating the problem. An attempt to curb the rapidly increasing membership to paramilitary organisations saw Northern Ireland’s Unionist government, backed by their British counterparts, introduce internment without trial in 1971, one of the most notorious and fundamentally damaging policies of the era. The law gave the British army the unprecedented power to arrest and detain anybody they deemed a threat to the stability of the nation. The mass operation saw 340 people from Catholic backgrounds arrested and questioned, many with little or no evidence of association with the IRA or other paramilitary organisations. Evidently, fury arose at the unjust subjugation of the Catholic community, despite paramilitary organisations existing on both sides of the divide.

Whilst IRA membership increased rather than declined as a result of internment, many people from nationalist communities sought peaceful means to oppose the law, and marches were orchestrated for the end of January 1972. It’s important to note that protests had been banned by the government in order to try and maintain order in a rapidly deteriorating climate. Thus, the reaction of the paratroopers sent to observe the protest on 30th January 1972 was one of force. Skirmishes broke out between a small minority of the marchers and British paratroopers, which was by no means an uncommon occurrence during this period. The resultant reaction of the British army was to open fire onto the crowd, in which 26 unarmed attendees were struck, and 14 killed. The reaction of the British government was to release a report 3 months later defending the actions of the paratroopers and taking no responsibility for the deaths of the innocent protesters. It was not until 2010 that the British government offered an official apology to the families and communities whose lives had been ripped apart by the event.

The event is one of the most well-recognised, well-documented events of the 20th century in both the Republic and North of Ireland. Lack of coverage and discussion has rendered understanding of the event in Britain completely redundant. It’s indicative of a serious lack of understanding of not just Irish history, but British history in Ireland, as well as its wider colonial past. Many British people, inspired by an education system that refuses to acknowledge the dark history of our country, see Ireland as our close-geographical neighbours who share similar language, cuisine and culture. There is an intense lack of understanding of not just the events of the Troubles, but the wider relationship between Britain and Ireland. Everybody in England can tell you how many wives Henry VIII had, but a vast majority would struggle to recall the events of Bloody Sunday.

British school history will repeatedly recount our importance in winning world wars and the glory of the past monarchies but refuses to educate our children on the damaging impact of our actions in Ireland and beyond. Common perceptions amongst people in Ireland are that the British are unaware of the history of their country in Ireland, as perpetuated by an establishment that neglects recognising its questionable past. Events so recent as the Troubles are not only misunderstood but greatly misconstrued in British culture. Everybody knows who the IRA are, but nobody knows why they came to exist, or about events such as Bloody Sunday which increased their sympathies in Ireland tenfold.

It’s a deeply shameful thought that our current political climate has prioritised thoughtless nationalism and favourable views on Empire over an attempt to understand the intricacies of our past. The current Brexit era, spurred on by the current Conservative government has encouraged further neglect of British history, in favour of jingoistic perceptions on the nation. Brexit has also made apparent the damaging impact of historical neglect on the stability of Northern Ireland. The Good Friday Agreement, an act essential to peace and stability in Northern Ireland, has come under great threat due to trade complications as a result of the British decision to leave the EU. British nationalism has not only undermined Irish history in its educational neglect, but now poses a very real, political threat to political stability in the region.

It’s only the slightest consolation, if any, that the families of the victims of the Bogside massacre were finally able to receive an apology from the British government almost 40 years after the events of 1972. The Troubles were an event that destroyed relationships and families across Northern Ireland, and a large responsibility for this must be taken by the British government. It is also essential that our public becomes more educated on the actions of our past governments in Ireland and other colonial acquisitions. The current Brexit era, spurred on by the current Conservative government has encouraged further neglect of British history, in favour of jingoistic perceptions on the nation.

Header Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons