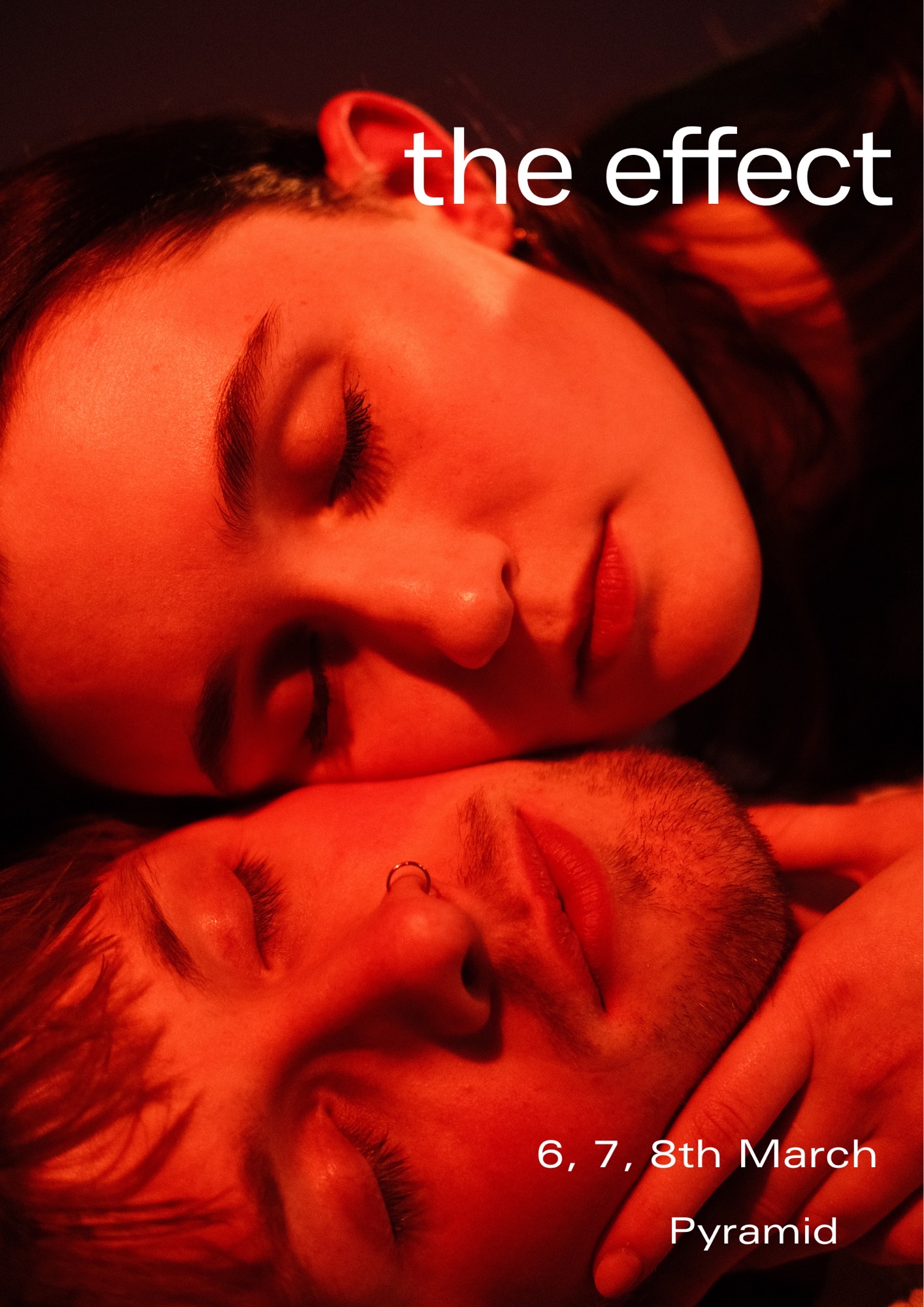

Review: ‘The Effect’

The Effect, directed by Erin Williams, opened on Thursday night at the Pyramid Theatre in the union. Williams’ adaptation of the play, originally written by Lucy Prebble in 2012, was highly accomplished and hit the mark in every aspect.

The premise is a love story set during a clinical trial. Tristan (played by Ben Harris) and Connie (played by Amalie Murray) are observed as they participate in a drug trial for a new antidepressant, both having previously suffered from depression. Isolated from the external world and sharing this unique experience, the pair begin to fall in love. However, as sexual activity risks compromising the trial’s results, their romantic affair is prohibited. The drug’s side effects – including impulsivity and impaired decision-making – leave Connie and Tristan with the mental torture of deciphering whether their feelings are real or merely a dopamine high and whether their relationship could survive beyond the confines of the experiment. They also grapple with the pressing question of whether one of them is on a placebo. The irony, of course, is that love itself is like a drug, producing heightened levels of dopamine and activating brain regions associated with opioid addiction. This thematic cocktail of drugs and romance leaves the audience unsure of who is genuinely in love and who may merely be under the influence.

Observing the patients is Dr Lorna James (played by Elana Lewis), a psychologist devoted to the success of the study. She often turns to the advice of her boss Dr Toby Sealey (played by Oliver Clark), a slightly insufferable but amusing senior psychologist. The two discuss the results of the study as it unfolds and its ethical concerns, while choosing to brush over their complex past which involved an affair and a painful breakup due to Dr James’ poor mental health.

The set of the Pyramid Theatre in the Union was sparsely decorated with props and furniture, reinforcing the clinical atmosphere of the play. Two mattresses lay on either side of the stage which, if split in half, was mirrored. They represent the participants’ living quarters and are positioned at the opposite end of the stage from the psychologists’ chairs, which occupy opposing corners. Dr James’ voice is played through speakers, at times advancing the plot, and at others communicating with the audience about fire exits and intervals. This effect was designed to immerse the audience in the context of the trial, and it was well-executed.

The script is full of punchy jokes, sarcasm, and relatable lines. The ability to move an audience to fits of laughter whilst balancing topics of a heavy and sensitive nature requires skill, which is exactly what this production delivered. The comedic timing was phenomenal, as well as the dynamism of the actors; the capacity of Dr James’ character to shift seamlessly between rigid and blunt in her professional role as a clinical psychologist, to an emotional, gripping display of vulnerability in a monologue about her personal battles with mental health and a self-deprecating inner dialogue, was immensely powerful.

Whilst scenes without Connie and Tristan left their part of the stage cast in shadow, symbolising their exclusion from events beyond the confines of the study, scenes featuring only Connie and Tristan kept Dr James and Dr Sealey’s position on stage consistently illuminated – reiterating a sense that the study’s subjects were under constant observation.

The scene which saw Tristan and Connie spend an evening entirely in one another’s company was a personal favourite of mine. Moving through the motions of a long night spent getting to know someone, they gave a relatable account of the earliest moments of a relationship: pillow talks, tender moments, shared stories about past relationships, family secrets, and giggles. It was evident that this scene caught the hearts of the audience, who were either laughing or held in captive silence.

The intensity of Tristan and Connies relationship was entirely believable due to the subtilties of their on-set chemistry, and their battle to be with each other during moments of paranoia and desperation felt Shakespearean. As their illicit relationship becomes prevalent to Dr James, they are separated, which turns these adults into petulant children, defiant and stubborn as if they were teenagers kept apart by a teacher.

I found Tristan and Connie’s frantic and anxious demeanour an uncomfortable and unsettling watch. Their demonstration of physical turmoil gave us a window into the state of minds of the characters, reeling with neurologically interfering drugs. This was intensified by contrasts in lighting, and the heavy, pulsing bass of the music, further amplifying the atmosphere of the room which felt tense and desperate.

Given that the script was written 13 years ago, the play remains keenly relevant in an era witnessing the exponential growth in individuals suffering from depression and anxiety. Dr Sealey’s revelation that he felt unable to be in a relationship with Dr James due to her own battles with depression reflects a situation many of us have witnessed in the lives of family and friends.

The Effect is a play about love, depression and medicine. As Connie and Tristan grapple with the question of whether the love they feel is a side effect of the anti-depressant, it can instead be reframed: the anti-depressant merely opens the door to something that was already there, giving the patients an equal opportunity to truly experience the phenomenal effects of love.